Pentagramma pallida Pilgrimage

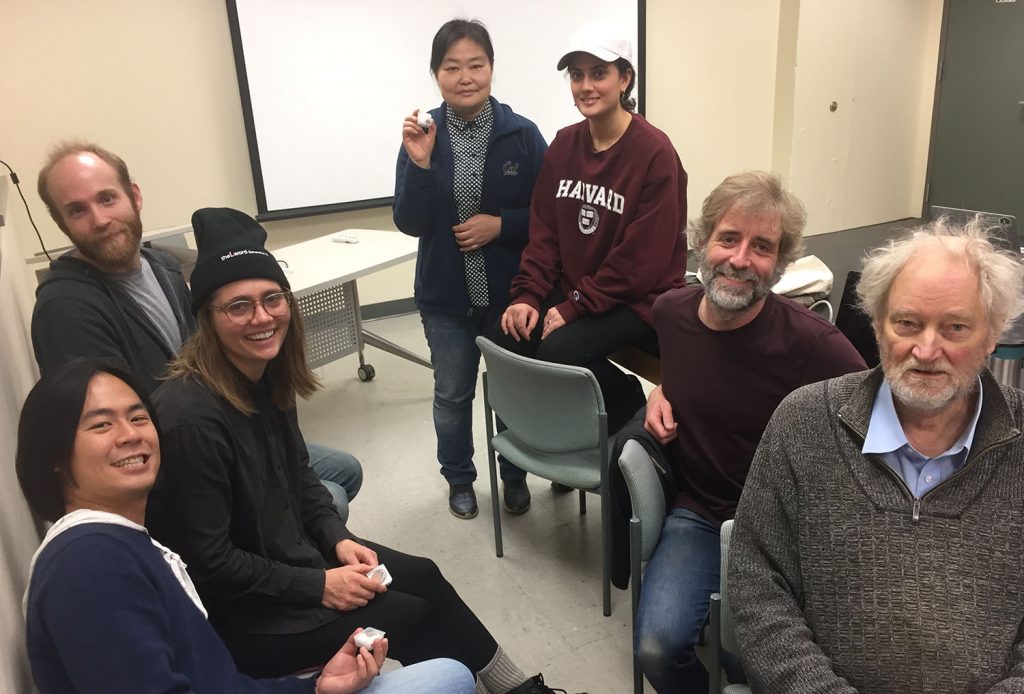

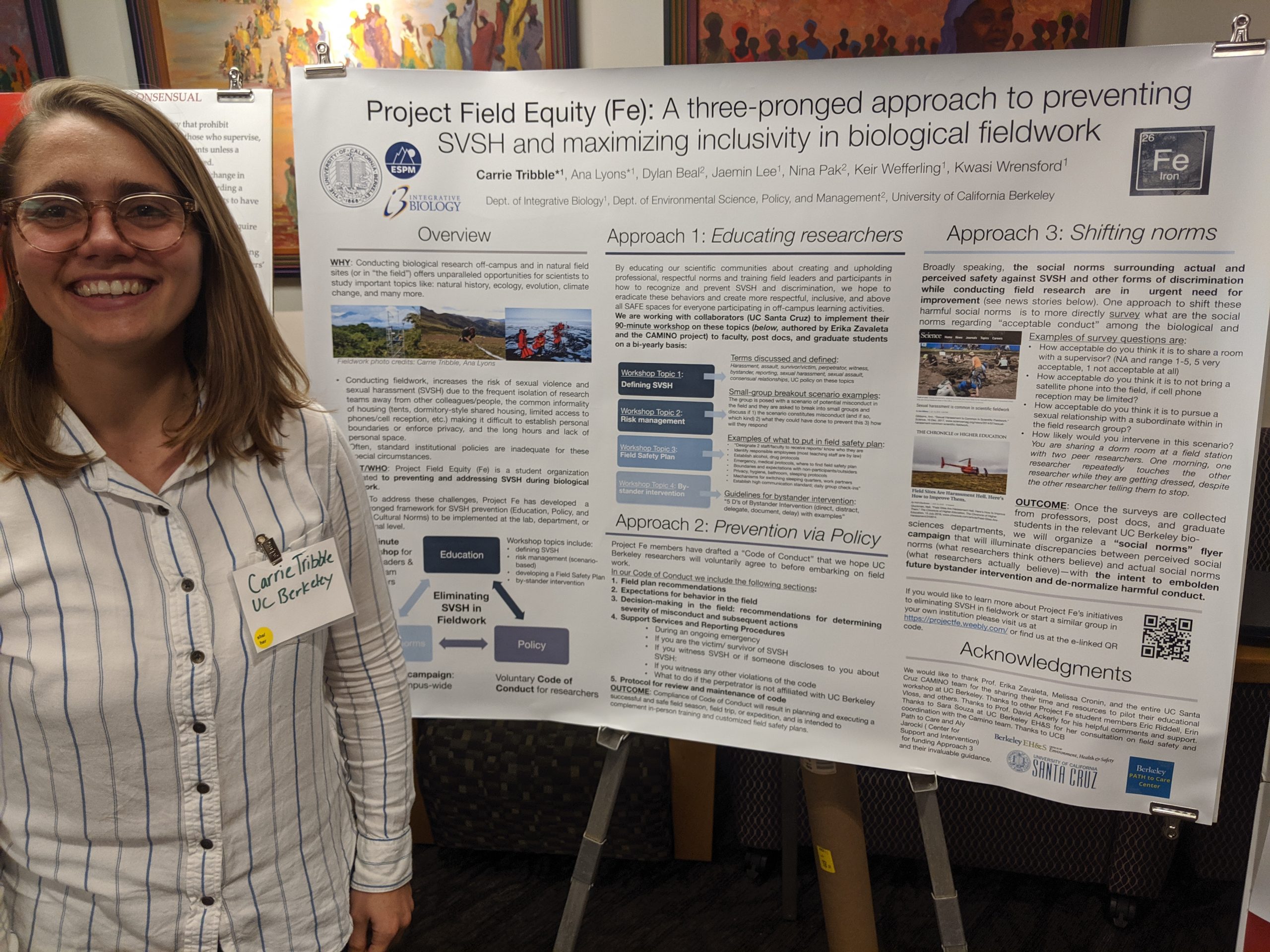

Based on a hot tip from Carrie Tribble, the Rothfels Lab set out one fine Sunday for the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Driving through rain, we gathered at Table Mountain trailhead (in Tuolumne County) for some general (plants!) and specific (Pentagramma pallida!!) botanizing. Isaac Marck made one or two iNaturalist observations for the day.

Avoiding—mostly—the gorgeous and diversely-lobed Toxicodendron diversilobum (Anacardianceae), we soon encountered our first fern of the day: Pentagramma triangularis ssp. triangularis (Pteridaceae, hemionitid clade of the cheilanthoids).

Another early highlight was Thysanocarpus curvipes (Brassicaceae)….

… soon followed by Aspidotis californica (another hemionitid) then Isoëtes nuttallii (Isoëtaceae; yay, Forrest!

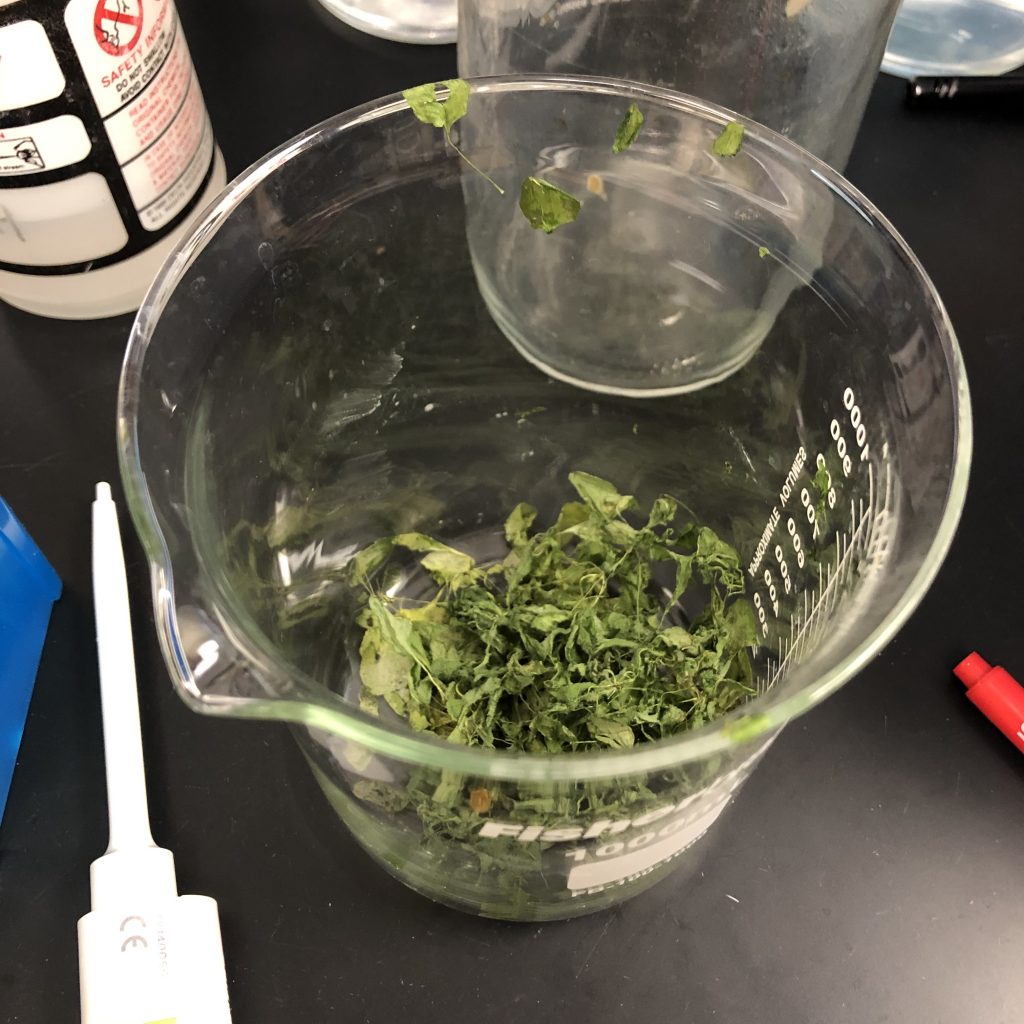

But, enough of that; we had driven these many miles not for these non-pallida plants. We were there to see—and collect—the California endemic Pentagramma pallida! So we followed Carrie towards the base of the cliffs of Table Mountain, specifically to the—according to Abby Jackson-Gain—porphyritic (i.e., with phenocrysts/feldspar) columnar basalt and basalt rubble. Nearby associates included Pentagramma triangularis, Quercus, Aesculus californica, Toxicodendron diversilobum, Diplacus aurantiacus, Selaginella hansenii, Myriopteris covillei (?), Pellaea mucronata, Ribes speciosa, and Streptanthus tortuosus. BUT, before we even reached the porphyritic zone, Keir encountered some very strange and wonderful Pentagramma with adaxial farina growing in chaparral, under Adenostoma fasciculatum, Toxicodendron diversilobum, Lepechinia calycina, and Heteromeles arbutifolia. He immediately and provisionally identified this highly distinctive (don’t laugh) morphotype as a hybrid (homoploid? allopolyploid?) between P. pallida and triangularis! The Ploidy Gods and Goddesses were smiling on the rlab that day, so we managed to collect immature sporangia at the right stage for meiotic chromosome counts; stay tuned!